Recently a colleague mentioned the 18th century philosopher Jeremy Bentham, and I was immediately left pondering why the connection between Bentham and social value calculation had never occurred to me before, and why Bentham’s ethical system has found its way into politics and economics, but not technology.

Bentham is primarily known as the founder of Utilitarianism, a branch of philosophy with the central tenet simply that ethics should be a calculation – when you aggregate it up, does the action in question bring more pleasure than cause pain?

It’s an appealing argument because it is both easy to understand – every human being comprehends pleasure and pain – and because it offers an independent test for adjudicating any moral action: for example, on a Monday morning the action which would bring me the most pleasure would be to put on my velour tracky bottoms and watch repeats of ‘Time Team’ with a big pile of toast and marmite, but I must weigh this against the agony my colleagues would endure at being denied my scintillating acumen and boyish charm. So I go to work.

Some obvious arguments against Utilitarianism do immediately present themselves – the citizenry of ancient Rome might have aggregated more pleasure from watching Christians being fed to lions than the Christians suffered by being eaten, but even the most committed utilitarian wouldn’t lobby for bringing back the gladiatorial games. To put this counter-argument mathematically: the sum of a collection of values doesn’t care how those values are distributed.

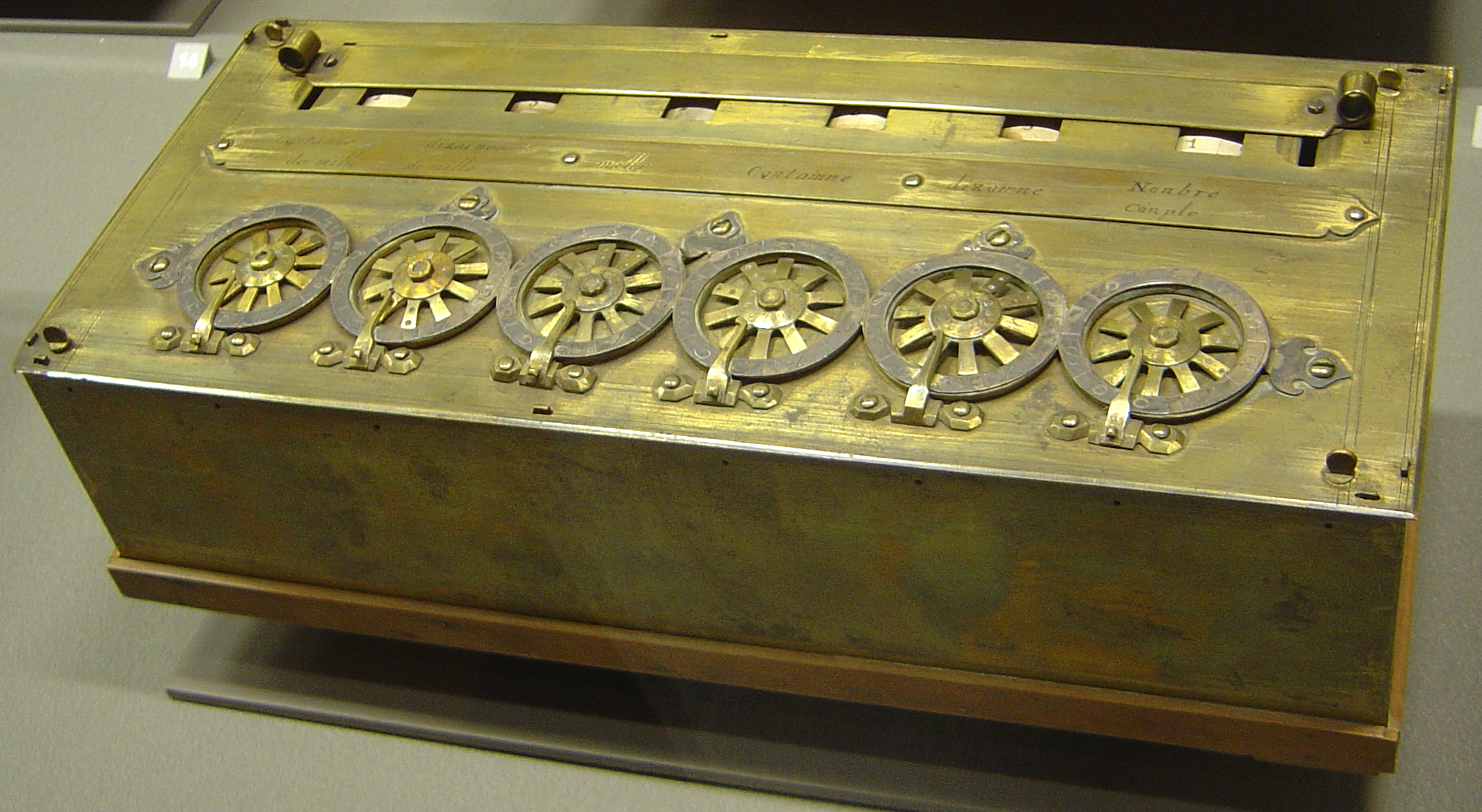

Bentham himself went so far as to invent a literal calculator for his method, which he gave the extravagantly deranged 18th century moniker of ‘The Felicific Calculus’ (a link to a digital version created by a student of philosophy can be found here, which apparently follows Bentham to the letter).

Bentham’s ornate vocabulary makes the conclusions that he reached using his method appear all the more startlingly modern. Born in 1748, in most respects Bentham was several decades if not centuries ahead of his contemporaries in philosophy. He abhorred slavery (“the foulest and most appalling leprosy”), he argued in favour of female suffrage nearly 150 years before the argument was won, and he wrote the earliest known English-language argument for the decriminalisation of homosexuality, on the entirely reasonable grounds that if it causes nobody any harm, it shouldn’t be illegal.

(Bentham’s method also led him to conclude that Oxford and Cambridge Universities were “the two greatest public nuisances”, an observation that I set down here without comment).

But the quote I found most intriguing was this from 1789 – the year, incidentally, of the French Revolution – when Bentham wrote: “The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”

This quote struck me as being almost satirical, as I feel I’ve heard it before from podcasters and public intellectuals in relation to potential artificial consciousnesses that human beings might create – we know that algorithms can already reason, after a fashion, and they can certainly talk, but whether they will have the capacity to suffer is something which (apparently) keeps awake at night many people of far greater intelligence and understanding than me.

This preoccupation seems to me rather odd, given the suffering that humanity already permits for non-artificial creatures, from child labour to factory farming to habitat destruction, none of which seem to invite public defence, and yet still proliferate. Given how much of our lives are now shaped by digital engagement, it doesn’t seem like a completely radical idea that the algorithms which monitor and hector and cajole us every waking hour, could be programmed with a view towards alleviating suffering, or at least given a nudge in Bentham’s direction.

While we instinctively recoil from any notion of ‘gaming the system’ in this way, especially so that algorithms might attempt to modify human behaviour on the say-so of some 18th century whinging lefty, it’s worth remembering that of course, the system is gamed already, but not in any pursuit of justice and fairness, nor of freedom of speech or even to push the bizarre political affiliations of silicon valley robber barons (not ordinarily, anyway), but these algorithms are designed for one purpose only: engagement.

Engagement is morally agnostic, and the algorithms do nothing except blindly optimise to keep users on their platforms (and available to consume advertising) – as many bums on as many seats, for as long as possible. Emotion is the greatest motivator of human beings, and cute cat videos will only get you so far – what really keeps people watching, clicking, and scrolling, is outrage. If you activate a person’s fight or flight response, they won’t put down their phone and go and do something else.

So contentiousness rules the internet, and Jeremy Bentham turns in his grave (if he had one, which he doesn’t – his corpse is preserved at University College London, Bentham died as he lived by bequeathing what was useful of his mortal remains to science, and what wasn’t to amuse his friends – one can only assume that your dead friend’s head pickled in a jar passed for entertainment before the advent of netflix). Our lives are mediated through screens, and we become twitchy, tribal, vain, distrait, and afraid, and the harder we all pull, the tighter the knot becomes.

Given how sophisticated the algorithms have become, and how constricting the feedback loops are on user engagement, including a ‘felicific calculus’ in the algorithm’s coding – an aggregation of the suffering any given piece of digital information might cause or alleviate – is a financial and legal, rather than technical, challenge.

(I should note that I’m aware of the irony that this notion stumbles headfirst into the quintessential AI ethics problem: how an ambiguous directive to “alleviate all suffering” could lead a literal-minded AI to catastrophic conclusions like mass euthanasia. As Joseph Campbell noted, “Computers are like old testament gods: all rules and no mercy.” Context always matters.)

Imagine an internet where every swipe and recommendation was audited for whether it would do any good, rather than whether it was likely to keep a user’s attention. These algorithms could and should be neither a deity nor a slave nor a tormentor, but simply an accountant.

Update, 12/09/2025: Sir Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the world wide web, articulates some of these themes in this recently released short video interview.