The funding landscape for charities and social enterprises is under extreme pressure. Demand is rising, costs are climbing, and established organisations are struggling to keep vital services open. The recent closure of several Samaritans branches exposed the harsh reality of this financial squeeze, with services withdrawn despite record levels of need.

Against this backdrop, funders and commissioners are placing increasing emphasis on collaboration. The National Lottery Community Fund, for example, has made partnership working a central plank of its grants strategy, stating explicitly that “working in partnership can achieve a greater impact” and creating programmes specifically for collaborative bids.

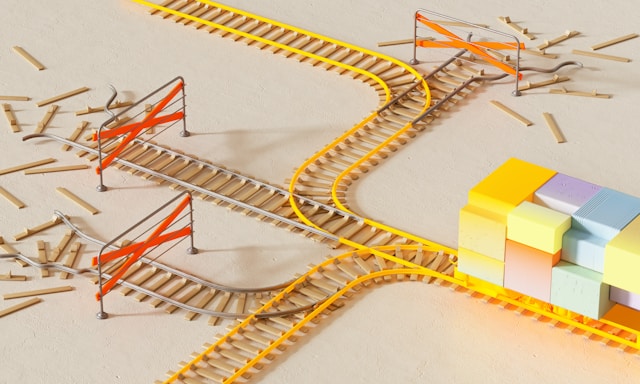

When misalignment undermines impact, and when it strengthens it

Collaboration, however, brings risks when alignment is absent. The UK government’s Work Programme was built on a large network of contractors and subcontractors, intended to bring together different capabilities. However, the National Audit Office found that providers tended to prioritise people who were easier to support into work and gave less attention to those with more complex barriers. The result was that vulnerable groups did not always receive the help they needed, and partnerships designed to increase reach sometimes ended up reinforcing inequality.

A similar challenge has been documented in efforts to integrate health and social care services in England. Reports by the King’s Fund describe how differing organisational cultures, governance arrangements, and accountability frameworks often undermined joint working, creating friction between NHS trusts, local authorities, and voluntary sector partners. What looked like collaboration on paper frequently broke down in practice because alignment in purpose and measurement was missing.

Examples of stronger alignment can be found in community wealth building initiatives in Scotland. Councils have worked closely with housing associations, local charities, and other “anchor institutions” to redesign procurement in ways that maximise local economic and social value. What set these partnerships apart was the investment in early dialogue to agree shared priorities. By the time bids or delivery plans were produced, the partners had already aligned around purpose, values, and outcomes.

Tools and practices that help

Alignment does not happen by default, but there are tools that make it more likely. Collaborative Theory of Change workshops are used by funders such as the National Lottery Community Fund to help partners co-design projects and surface assumptions early. Guidance for community organisations, such as that produced by Locality, stresses the importance of being honest about differences and potential conflicts early on.

Measurement frameworks are another area where alignment matters. Social impact methodologies such as Social Return on Investment and platforms like the Social Value Engine provide shared language for evidencing outcomes, reducing the risk of competing claims within a partnership and grounding delivery in the perspectives of stakeholders.

Alignment as an ongoing commitment

Even well-aligned collaborations require maintenance. Successful partnerships schedule regular opportunities to revisit shared goals and re-examine whether reporting frameworks still reflect community needs. Without this discipline, initial alignment risks eroding, leaving partners working at cross-purposes.

Current funding trends reinforce the need for authentic collaboration. The National Lottery Community Fund continues to prioritise partnerships, Better Society Capital has now channelled more than £1 billion into social impact programmes that often rely on cross-sector partnerships, and the UK government’s Better Futures Fund has been designed from the outset as a £500 million collaborative programme for youth services, combining contributions from public, private, and third-sector partners, with outcomes used to drive returns.

Conclusion

Charities and social enterprises can no longer rely on single-organisation bids in many areas of funding. Collaboration has become both an expectation and, increasingly, a condition of access to major programmes. Yet collaboration that is rushed or imposed can do more harm than good. The strongest examples—from community wealth building to integrated care—show that alignment in purpose, values, and measurement is what makes joint working succeed.

In a funding environment where survival depends on collaboration, alignment can make the difference between partnerships that unlock new opportunities and those that collapse under the weight of good intentions.